OP-ED - After the launch party: who actually benefits from AI?

What gets measured depends on who builds the scale.

Last week's piece examined what survives the AI agent layer collapse — the gap between automating tasks and enabling purpose. But survival is one question. Who benefits is another. And cue Part 2.

Two recent publications offer competing lenses on AI's economic promise: The Anthropic Economic Index Report, a data-driven analysis of how people actually use Claude; and Stephen Deng's "Africa’s Narrative Lock-In" essay, a venture capitalist’s (VC) diagnosis of why African tech is stuck telling the wrong stories.

Both contain useful observations. Both are shaped by the interests of those producing them.

The Anthropic data

Anthropic's Economic Index white paper landed in mid-January 2026, within days of the company shipping Claude Cowork — the desktop automation feature that prompted Eigent to open-source itself.

The timing is instructive. The report provides empirical framing for a product launch: here is what AI does for the economy, published days after here is what our AI can now do on your computer.

This doesn’t make the data invalid. It does mean the data arrives loaded with corporate messaging intent.

The report draws on millions of Claude conversations to map AI usage patterns across occupations, geographies, and task types. It is one of the few empirical datasets we have on how AI is actually being used in the wild — which makes it valuable, and worth interrogating.

A few findings stand out.

First, the report identifies a stark divergence between API usage (overwhelmingly automated, back-office tasks) and Claude.ai usage (augmented human-in-the-loop collaboration). This supports the "task versus purpose" distinction unpacked in Part 1: the task layer is being commoditised; the purpose layer still requires human judgment.

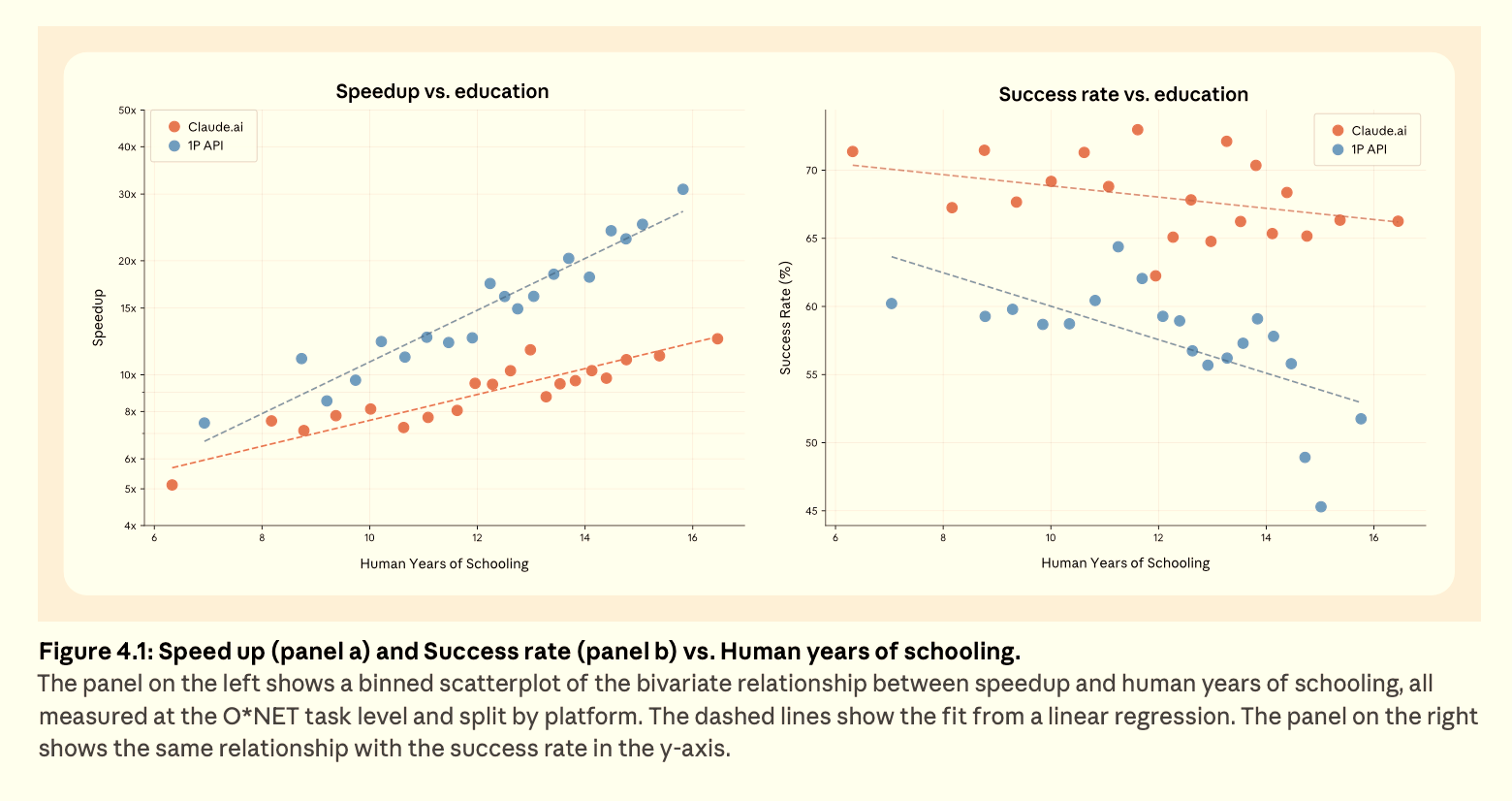

Second, and more troubling: the report finds a near-perfect correlation (r > 0.92) between the "education level" of a user's prompt and the "education level" of Claude's response. In plain terms: sophisticated inputs yield sophisticated outputs. Unsophisticated inputs yield less.

Anthropic essentially frames this as AI meeting users where they are. A more sceptical read: AI is skill-locked. If you cannot articulate a sophisticated prompt, you cannot extract sophisticated value. The model mirrors your limitations back at you.

Third, global AI adoption is "persistently uneven" and strongly correlated with GDP. High-income countries use AI more, but (counterintuitively) delegate less autonomy to it. They treat Claude as a collaborator, not a replacement. Meanwhile, in lower-income countries, a leading use case is coursework: educational help, not industrial acceleration.

The "leapfrog" narrative, once again, looks overstated.

A different read from Delhi

Not everyone accepts the "second tier" framing for emerging economies.

At Davos last week, India's Ashwini Vaishnaw - who holds the electronics, IT, and broadcasting ministerial portfolios in the Modi government - pushed back on the International Monetary Fund's (IMF) framings that place India as a follower rather than a leader in AI.

His argument echoed Jensen Huang's five-layer framework, but inverted the emphasis. "ROI doesn't come from creating a very large model," Vaishnaw told the "AI Power Play, No Referees" panel at the World Economic Forum. "95% of the work can happen with models which are 20 billion or 50 billion parameters."

India's play, he argued, is the application layer: going to enterprises, understanding their business, deploying AI to increase productivity. "That's going to be the biggest factor of success."

It is the same bet Papermap is making at the startup level — and a direct challenge to the skill-lock thesis. If application-layer value is where ROI lives, and if India (or say South Africa, Egypt or Nigeria) can build the "Doing" infrastructure that turns abundant models into real outcomes, the GDP-correlation story may be more contingent than Anthropic's data suggests.

Stanford's Global AI Vibrancy Tool, Vaishnaw noted, places India near the top globally, including second on some AI talent metrics and roughly third on overall AI vibrancy.

Whether ministerial assertions at Davos translate to ground-level reality is, as always, a separate question.

The VC diagnosis

Meanwhile, Stephen Deng's "Narrative Lock-In" essay arrives at a similar place from a different angle. Deng is a general partner (GP) at DFS Lab, an early-stage fund focused on African fintech. He has spent over a decade investing on the continent, backing more than 50 startups including Andela and NALA, and previously worked on the Gates Foundation's financial services for the poor team.

His argument: African venture capital has been telling two stories for the past decade — the Population Narrative (Africa's young, digitally-native workforce) and the Purpose Narrative (double-bottom-line impact). Both stories unlocked capital. Both, Deng contends, are now exhausted.

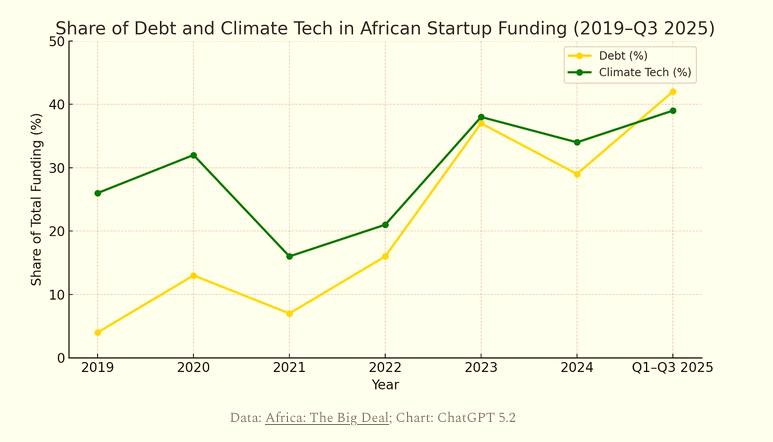

He cites striking data. Debt now represents 42% of African startup funding — an all-time high. Climate tech accounts for 39%. Equity deals have stagnated. Pre-seed funding has collapsed, with Deng noting that in Kenya, roughly half of 2025 pre-seed rounds are grant-based.

Deng's prescription: "impatient capital" that demands global leverage rather than patient returns tied to demographic destiny.

It is a handy observation about where the VC conversation is. It is also, transparently, a story designed to position his next fund. GPs need narratives to raise from limited partners (LPs). How true those narratives need to be is a separate question.

The skill-lock problem

Here is where the two analyses converge — and where Papermap, the startup profiled in Part 1, becomes interesting again.

Anthropic's data suggests that AI's economic value is gated by input quality. If your prompts are unsophisticated, your outputs will be too. Deng's essay suggests that African venture is gated by narrative exhaustion. The old stories no longer unlock capital; new ones have not yet emerged.

Both point to the same structural problem: the "Missing Middle". The businesses too small for enterprise AI, too unsophisticated for the Modern Data Stack, too resource-constrained for the patient capital thesis — and now, potentially, too skill-locked to benefit from generalist AI tools.

Papermap's wager is that you can build a "Doing" layer that compensates for this. A system that does not assume clean data, educated prompts, or a data team. That builds for chaos.

It is one answer to the skill-lock problem. Whether it scales is yet unproven.

The critical lens

A journalist's job isn’t to validate any of these narratives, but rather to track what each party has an interest in claiming.

Anthropic has an interest in demonstrating that AI is economically useful, broadly adopted, and increasingly essential. Their report emphasises productivity gains while soft-pedalling the skill-lock implications.

Deng has an interest in diagnosing African venture as stuck. Because if it is stuck, it needs a new story, and he is selling one.

Papermap has an interest in positioning itself as the solution to a problem that may or may not be as acute as they claim.

None of this means they are wrong. It just means their claims should be weighed against their incentives.

What remains

The Anthropic data reveals something awkward: AI's benefits may accrue disproportionately to those already equipped to extract them. The educated, the articulate, the well-resourced.

Deng's diagnosis reveals something equally uncomfortable: the stories we tell about African tech may have more to do with what LPs want to hear than what is actually happening on the ground.

Both observations can be true simultaneously. Neither offers a clean prescription.

What remains is a question: if AI's economic impact is skill-locked and GDP-correlated, and if African venture's dominant narratives are exhausted, what story actually fits the facts?

That is the sensemaking work still to be done.

Editorial Note: A version of this opinion editorial was first published by Business Report on 27 January 2026.