OP-ED: Secha Capital’s Operator-Investor Model—An African VC alternative breaking the tech-first mould

Amid Janngo Capital's oversubscribed final close and Techstars’ abrupt exit from Lagos, Secha Capital champions South Africa’s traditional industries with a slow-burn, hands-on investment model—reshaping venture capital norms.

The closing quarter of 2024 has so far delivered some telling indicators of Africa's evolving investment landscape.

While Nigerian fintech Moniepoint reached a unicorn valuation with its $110 million Series C and Fatoumata Bâ and Co’s Janngo Capital achieved an oversubscribed $78 million final close, Techstars' sudden withdrawal from Lagos—after reportedly deploying roughly $2.4 million across 24 startups in just two years—has triggered sobering conversations about ecosystem sustainability.

Contrarian sensibilities

This juxtaposition of fortunes took me back to a stimulating social media exchange I had in early 2018. Two former Bain & Company consultants, Rushil Vallabh and Brendan Mullen, who had departed the firm in 2016 to establish Secha Capital in South Africa alongside Nombuso Nkambule, reached out on Twitter to share perspectives on early-stage venture investment themes we'd been unpacking on the African Tech Roundup podcast. What struck me wasn't merely their engagement with our content, but rather their distinctly contrarian investment thesis when African tech VC euphoria was reaching fever pitch.

Slow-burn validation

While many VCs were racing to back pure technology plays, Secha Capital was quietly building an operator-investor model focused on traditional industries—a stance that drew equal measures of scepticism and curiosity from market observers.

More recently, the R300 million first close of the firm’s second fund in September 2023, backed by institutional heavyweights like RMB Ventures, SA SME Fund and 27four Investment Managers, suggests there might be merit in their measured approach.

Notably, Secha's hands-on operator-investor model preceded by several years the venture building support approach now gaining widespread traction among African tech VCs—a shift that seems to validate their early recognition of the continent's unique entrepreneurial support needs.

As Africa's tech ecosystem navigates the sobering aftermath of the 'grow-at-all-costs' era, with various high-profile failures forcing a rethink of conventional venture capital models, it seems an opportune time to reflect on what it might take for investors to bridge Africa’s ‘real’ and digital economies.

In this week's TechTides column hijack, Secha Capital's co-managing director Vallabh teams up with one of his firm’s current operator-investors, Masedi Madisha, to share dashboard insights gleaned from over eight years of putting their thesis to the test.

Rushil Vallabh and Masedi Madisha’s insights. In their words:

When Secha Capital co-founder and co-managing director Brendan Mullen was asked in a recent Center for Global Development Growth Summit panel discussion what he'd do to increase productivity gains for developing economies, his answer caught many off guard. Instead of the expected responses about improved infrastructure, subsidised connectivity or enhanced nutrition programmes, he offered a different perspective drawn from our experience: aligned incentives.

This answer stems from our journey as investors in Africa's traditional industries. When we founded Secha Capital, we took what many considered a contrarian approach—one we've dubbed our "narrative violation"—by focusing on established, often overlooked sectors while others chased pure technology plays. As former management consultants, we viewed technology not as an end in itself, but as a crucial lever for growth and efficiency in traditional businesses.

Investment thesis evolution

The iteration of our anchoring thesis has been instructive. From initially avoiding pure tech investments, we've developed a nuanced understanding of how technology can transform traditional businesses when properly integrated with local market realities. This perspective has been shaped by our role as operator-investors, working hands-on with entrepreneurs to accelerate growth in ways that capital alone cannot achieve.

We've observed a stark contrast between our approach and traditional venture capital models, particularly in the African context. Consider the recent wave of high-profile failures: Sendy's logistics platform in Kenya, Pakistani Airlift's quick commerce solution, and even the struggles of Indian edtech giant Byju's. These cases highlight the limitations of the "hyper-scale, grow-at-any-cost" mentality when applied to developing markets.

Context matters

The challenge lies not in the technology itself, but in how we deploy it. The standard VC playbook – making multiple bets with the expectation that a few massive winners will offset the losses – often overlooks critical African contextual factors. Infrastructure limitations, varying levels of tech adoption, extreme inequality, and complex regulatory environments all demand a more nuanced approach.

HouseMe's choppy experience in South Africa perfectly illustrates this disconnect. Despite raising over $3 million and building a user base of 50,000, the digital rental platform ultimately couldn't sustain its operations.

As detailed in a book entitled "The First Kudu," HouseMe’s founders relate discovering that success in the African market requires much more than being an "efficient, cost-effective, tech-based platform." They needed to become a full-service operation—handling tenant screening, maintenance, legal mediation and financial services—all whilst navigating infrastructure and policy limitations.

Reimagining fund structures

This brings us back to our thinking about incentives and productivity gains. The traditional 10-year fund structure pushes for quick scaling and exits, often at the expense of building sustainable businesses. At Secha Capital, we've taken a different approach, constantly asking ourselves: How do we align incentives across fund managers, portfolio companies and employees to achieve longer-term, sustainable returns?

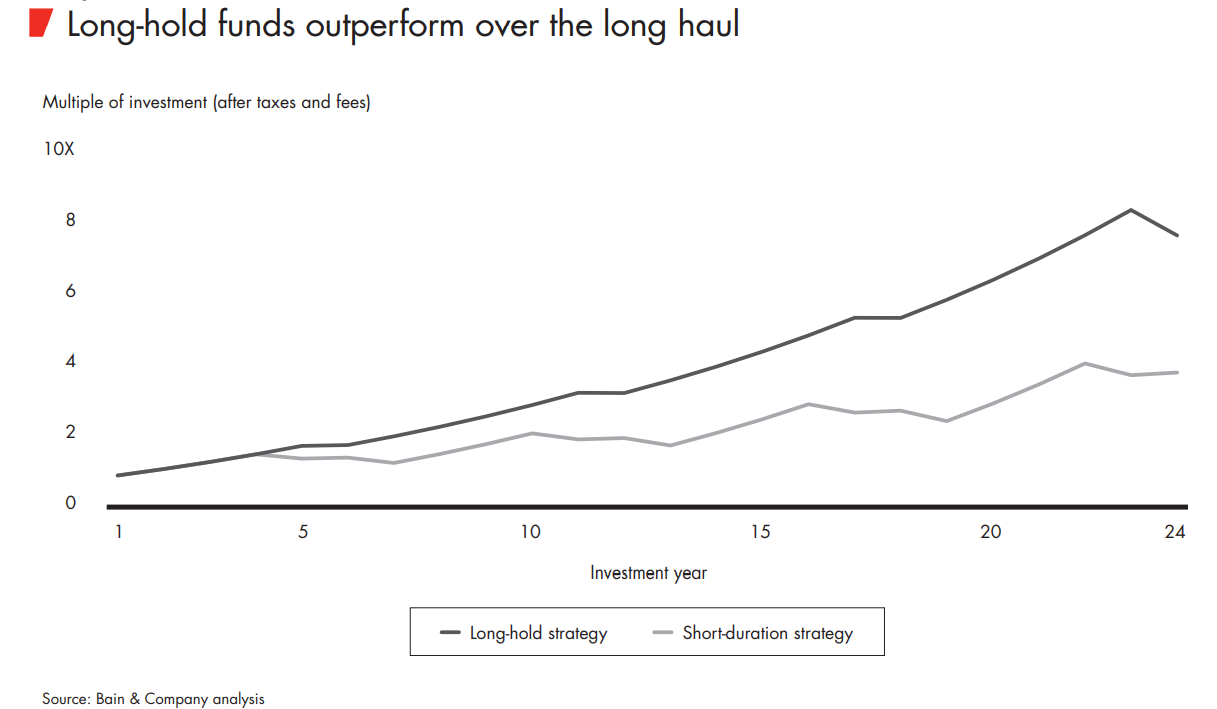

Research supports our perspective. Bain & Company studies show that long-hold strategy funds outperform short-duration funds by 2-3x. This longer horizon enables lower costs, more flexible decision-making, fewer portfolio company distractions and better alignment between investors and investees. It's fundamentally changed how we approach innovation and impact measurement.

ESG: From checkbox to core strategy

We've found this particularly relevant when considering Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG). By incorporating a 20-year outlook alongside typical fund lifecycles, we’ve positioned environmental impact, social responsibility and governance as core elements of our investment thesis, rather than as simple compliance checkboxes. We believe long-term productivity isn't just about quarterly metrics—it's about building businesses that can sustain growth while adapting to changing market conditions and societal needs.

A crucial element in our approach is enabling employees to participate in the value-creation cycle. Every Secha investment includes an Employee Share Option Pool (ESOP), allowing workers to build genuine wealth through equity ownership.

The response has been telling: when given the choice between cash bonuses or equity, our portfolio companies' employees chose equity 90% of the time. They want to participate in their company's long-term success, and this alignment drives productivity and innovation from within.

Bridging traditional and digital economies

As the late vice chairman of Berkshire Hathaway Charlie Munger once famously quipped, "Show me the incentives, and I'll show you the outcome."

In our experience with Africa's developing economies, productivity gains don't come from simply importing Silicon Valley models or throwing money at pure technology plays. They come from aligning incentives across all stakeholders—investors, operators and employees—while building businesses that understand and address local market realities.

We believe this approach bridges the gap between Africa's traditional and digital economies, creating sustainable businesses that can drive real productivity gains. It's not about choosing between technology and traditional business models—it's about finding the right balance and ensuring all participants are incentivised to build for the long term.

Editorial Note: A version of this opinion editorial was first published by Business Report on 05 November 2024.