OP-ED - A son's grief and gratitude in a world of unequal healthcare

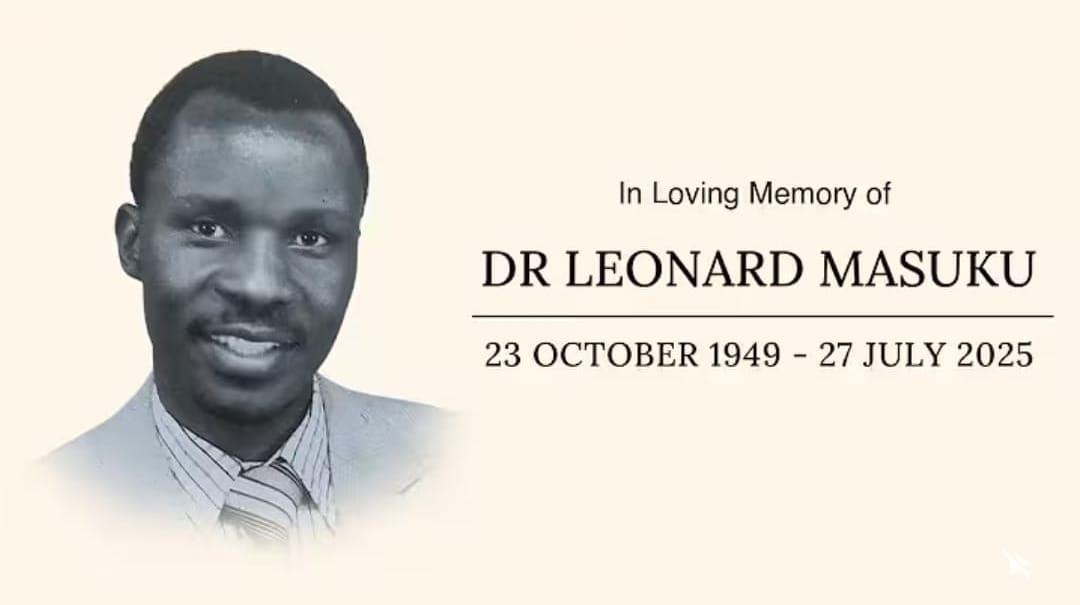

Dr Leonard Masuku's death within Zimbabwe's constrained hospital system serves as a stark reminder of healthcare's global inequities.

Three weeks ago, my wife Sithabiso and I were at a private medical facility in Jakarta, marvelling at what might be the most efficient care I've ever experienced.

Following streamlined pre-consultation rituals and a thorough half-hour session with a passionate dermatologist, my niggling adult eczema which was in beast mode was properly diagnosed and treated, clearing completely within a week and leaving me with empowering education about my condition. The UK's National Health Service (NHS), competent though they were in serving me, had barely managed the same through frustratingly cautious, iterative protocols over several weeks.

Our work trip was interrupted by devastating news: my father had been rushed to hospital after suffering what we would later discover was heart failure. The irony wasn't lost on me. Here I was, accessing impromptu premium private care all medical tourist-like, treatment that most Indonesians couldn't dream of affording. Meanwhile back home in Zimbabwe, Dr Leonard Masuku (aka Baba, Dad, The Bali to my brothers and I) was facing a medical crisis where even relatively privileged healthcare access couldn't guarantee optimal results.

The week prior, Sithabiso had travelled to Bali for the 2025 International Health Economics Association Congress (IHEA Congress), the premier global forum where researchers present findings on everything from public service quality to strategic financing reforms. I'd tagged along, ahead of us both heading to Indonesia's heaving capital on business.

The timing felt almost cruelly apt. In the wake of the worldwide health economics community debating optimal resource allocation and efficiency gains, news reached us that my father's condition had deteriorated rapidly. We cut our trip short and flew to Zimbabwe.

What followed was a sobering education in the brutal mathematics of medical provision under strain, culminating in one of the saddest days of my life. Arriving at Bulawayo's Mater Dei Hospital just minutes after my father had been declared dead in the facility's ICU ward.

My father's story isn't unique, but it's achingly personal. Dr Leonard Masuku had spent decades as a steward of others - from pioneering roles as the first black African chief financial officer within the Seventh-day Adventist Church in Zimbabwe and senior regional administrator across several Sub-Saharan African nations, to his years as finance director and academic dean at Solusi University. Yet he faced his final health challenge in less than ideal circumstances.

Despite helpful (but limited) post-employment medical aid coverage, proximity to better facilities, and a daughter-in-law with health economics literacy, treatment delays, lax personal stewardship and suboptimal care coordination contributed to an outcome that felt both inevitable and preventable.

The NHS's preoccupation with overtreatment prevention, which I'd initially found grating during my recent skin treatment, suddenly seemed like top-drawer medical provision by comparison. In Zimbabwe, undertreating often isn't a choice, it's literally what the establishment can provide. In Indonesia, my temporary brush with premium care highlighted how, for most of the world's citizens, medical treatment is a luxury good rather than a fundamental service available to all.

Dr Ikpeme Neto, the Nigerian physician-entrepreneur whose WellaHealth tackles medical financing across West Africa, recently shared a vulnerable moment from outside Lagos's National Hospital via X:

"I accompanied my grandma to National Hospital yesterday. If I talk now, people will say I've come again. Let me just hold my peace."

His holding of tongue spoke volumes about the institutional failures most Africans (and dare I say, most privileged global citizens) witness but struggle to articulate without seeming repetitive or complaining.

I accompanied my grandma to National Hospital yesterday. If I talk now, people will say I've come again. Let me just hold my peace. We and our families will all experience Nigerian healthcare together. When it's your turn, I pray it works out well for you. pic.twitter.com/FXxGNvzlAm

— Neto (@docneto) July 23, 2025

When I replied about going through "similar humblings" with my parents in Zimbabwe, his response was: "It's tough man! I pray similarly for your parents that they recover and do well!"

Neither of us knew then that my father's story would end differently. But that exchange reminded me that these aren't abstract policy or public health delivery failures; they're personal losses compounding across families, communities, nations.

In Zimbabwe, physicians trained to international standards work within infrastructure and clinical practice culture that doesn't engender positive results. Even patients with medical insurance face treatment delays that wouldn't occur in functioning establishments. Those without insurance face impossible choices between financial ruin and clinical neglect.

The NHS's methodical approach to treatment, which appears to require patients to return for iterative care rather than providing full-throttle intervention upfront, reflects resource-conscious medicine. But it also places the burden of care coordination on patients and families, a burden that becomes impossible when institutions lack basic functionality.

Indonesia's private medical efficiency impressed me, but it exists alongside a public structure that serves most Indonesians with far fewer resources. These parallel arrangements aren't sustainable solutions; they're manifestations of inequality that happen to benefit those with purchasing power.

Standing at my father's funeral service, I was struck by how health economics feels abstract until it becomes devastatingly personal. However, simultaneously, the analytical tools we use to examine medical provision (efficiency, equity, quality, access) become mere academic jargon when someone you love is caught in the gaps between them.

If I didn't have my faith and trust in God's faithfulness to fall back on, I might otherwise despair at the institutional contradictions that make positive medical outcomes more the exception rather than the norm across geography and economic circumstance.

But perhaps that's where the work begins. Health economics shouldn't be an academic exercise removed from human consequences. It should be driven by the recognition that behind every efficiency calculation and resource allocation decision are families navigating impossible choices.

IHEA Congress presentations and deliberations are meant to inform policy papers and funding decisions. But the gap between research insights and implementation remains awkwardly wide, particularly in contexts where health establishments face multiple, overlapping crises.

In all my years of professional writing, I've never once referenced my father's work or legacy. But grief has a way of collapsing inhibition.

Addressing hundreds of mourners gathered at his funeral at Solusi University last week, with a couple of thousand more joining via livestream, I spoke of how Johann Sebastian Bach would sign off the manuscripts of his orchestral masterpieces with "SDG"—Soli Deo Gloria, Latin for Glory to God alone—understanding that any earthly achievement means nothing without that ultimate acknowledgement.

My father (with my mother Dr Elisa Masuku (PhD), his grieving wife of 50 years, by his side) promoted that truth (albeit imperfectly at times) from the minister's pulpit to boardrooms, from lecture halls to his beloved farm in Gwatemba; he closed every chapter with "Okwethu yikubonga"—our portion is to give thanks. Even facing medical establishments that couldn't, or indeed wouldn't, serve him well.

And so, with my heart sore but full of gratitude for the 41 years of his given 75 that I was blessed to have him as my father, I echo Baba's oft-spoken refrain: okwethu yikubonga. Soli Deo Gloria.

Editorial Note: A version of this opinion editorial was first published by Business Report on 12 August 2025.