OP-ED - Nudge, don't shove: what Australia's social media ban gets wrong

Prohibition makes for a satisfying sign. Behaviour change is messier.

Signing up for Vitality health insurance in the UK earlier this year taught me something about behaviour change that policymakers elsewhere might find instructive.

To earn two months of free medical cover under our joining promotion, my wife Sithabiso and I each needed to accumulate 48 activity points for two consecutive months.

Walking the talk

The maths is straightforward: walk 7,000 steps and earn 3 points. Hit 10,000 for 5 points. Push to 12,500 for 8. Sixteen days of moderate walking, or six days of serious effort, and a bunch of nifty shopping vouchers unlock alongside the discount.

No lectures. No prohibitions. Just a system designed to make healthy choices feel like wins.

And you best believe that S’tha and I met the mark and copped those freebies. We've also scored a handy habit boost to our regular walking regime that our future selves will no doubt thank us for.

S'tha, whose health economics research over the last decade has involved collaborations with behavioural scientists working on tricky issues such as medication adherence, calls these interventions "nudges." The term, popularised by US economist and Nobel prize winner Richard Thaler, describes choice architecture that steers behaviour without restricting options.

Mumbai's traffic police understood this when they installed decibel meters at congested intersections in 2019. If hooting exceeded 85 decibels, the red light timer reset, forcing impatient drivers to wait longer.

No new laws. No fines. Just consequences that turned the undesirable behaviour against itself. "Honk more, wait more," the signs read. Drivers got the message.

Australia's blunt instrument

Australia, by contrast, has chosen to shove.

From 10 December, platforms including Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, YouTube, X, Snapchat, and Reddit must take "reasonable steps" to prevent Australians under 16 from holding accounts.

Meta has already begun removing young users ahead of the deadline. Fines for non-compliant platforms reach AUD $50 million. There are no penalties for children or parents who circumvent the rules, but crucially, there's no parental consent exception either.

The state has decided that social media is so categorically harmful to developing minds that even informed parents cannot be trusted to make that call.

Notably, the legislation enjoys bipartisan support, roughly 77% public approval, and a growing queue of imitators. Malaysia announced a similar ban for 2026 within weeks. France is pushing for an EU-wide prohibition for under-15s. Denmark and the UK are circling.

A legal challenge has been filed by the Digital Freedom Project on free speech grounds, though its fate remains uncertain.

Reluctant sceptic

I find myself in an uncomfortable position: a reluctant sceptic of legislation confronting a challenge that’s dragging society down.

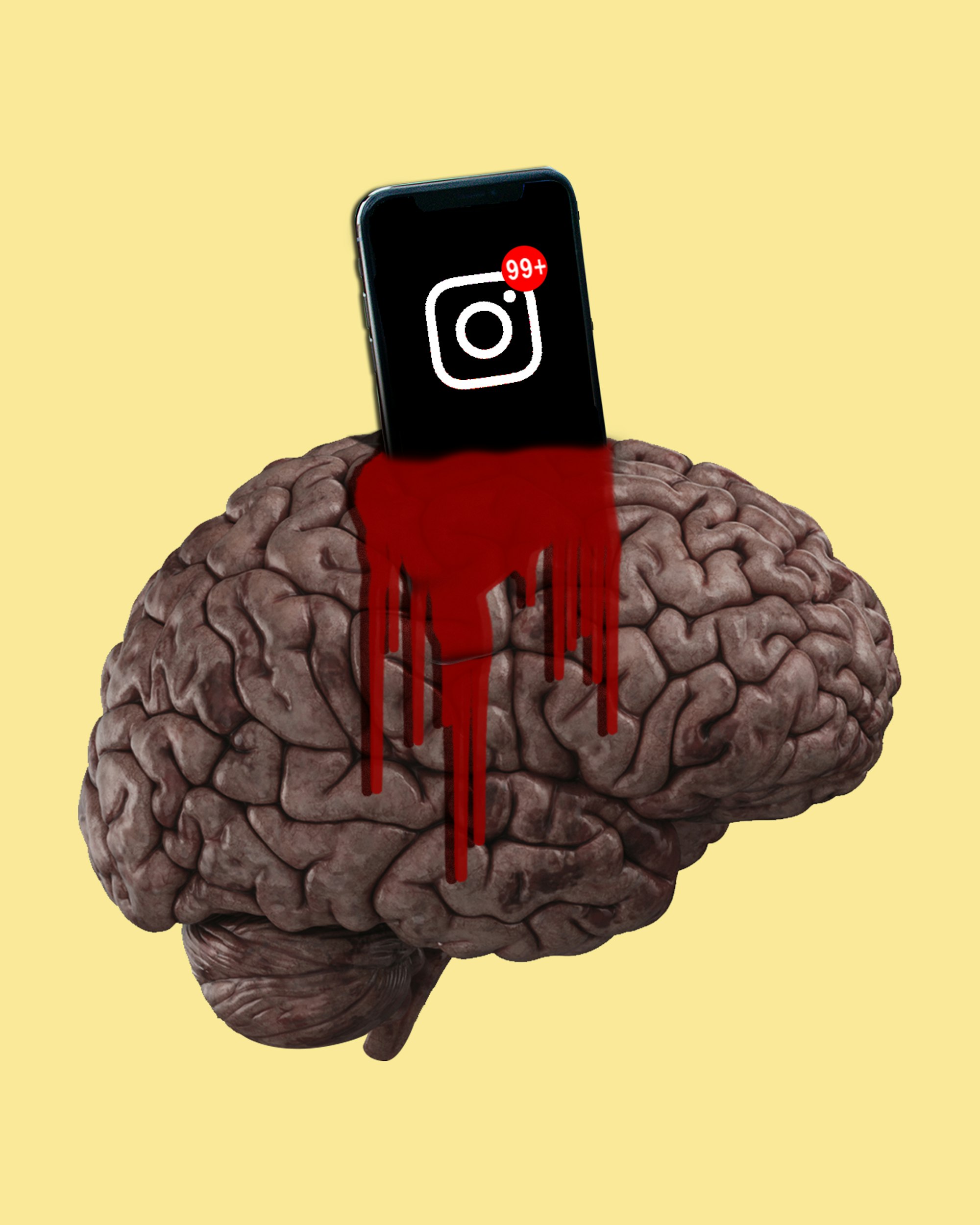

The concerns driving this policy are legitimate. The research linking heavy social media use to adolescent anxiety and depression is correlational rather than conclusively causal, but the pattern is consistent enough to warrant serious attention. Algorithmic feeds optimised for engagement do exploit developing brains. Cyberbullying finds fertile ground in spaces where children congregate. The eSafety Commissioner Julie Inman Grant isn't wrong when she describes this as a "tipping point".

It also grates me to watch parents encourage children to grow up in the public eye on social media, building entire family businesses around kids performing for the algorithm and cultivating celebrity brands in ways that don't appear to bode well for those children later in life. Whatever autonomy and privacy those kids might have had gets traded away before they're old enough to understand the transaction.

But prohibition is a blunt instrument, and this particular prohibition contains what strikes me as a tad hypocritical at its core.

Adult doom-scrolling

The same algorithmic mechanics that supposedly render social media unsuitable for a 15-year-old operate identically on a 25-year-old, or a 45-year-old. The dopamine loops, the infinite scroll, the engagement-maximising recommendation engines: none of these reset at some magical age threshold.

If these platforms are genuinely dangerous enough to warrant banning children outright, the question of why adults remain free to doom-scroll deserves a better answer than "they're old enough to know better." The policy protects the young from harms we're unwilling to address for everyone else.

I'm generally wary of legislating morality, mind. You cannot sustainably solve problems that fundamentally stem from poor self-regulation through prohibition alone, especially absent the patient, difficult work of actually building capacity for that self-regulation.

This is partly why nudges interest me. They work with human psychology rather than against it, creating environments where better choices become easier choices.

Nudge, nudge

What might a nudge-based approach to youth social media look like?

Platform-level interventions could include friction by design: mandatory pauses before posting, cooling-off periods for inflammatory content, usage dashboards that make consumption patterns visible and slightly uncomfortable.

Parental tools could evolve beyond crude screen time limits to more sophisticated systems that flag genuinely concerning patterns without infantilising teenagers.

Default settings for young users could prioritise chronological feeds over algorithmic ones, reducing engagement-maximisation pressure without eliminating access entirely.

None of this is as satisfying as a blanket ban. Nudges require patience. They acknowledge complexity. They don't generate headlines about "world-first" legislation or position politicians as child-safety champions ahead of elections.

African stakes

But they also don't throw out potential benefits with the harms. Social media, for all its pathologies, remains a genuine avenue for connection, creativity, education, and economic participation.

In African markets, where median ages hover around 19 and mobile connectivity is expanding rapidly, the stakes of getting this balance wrong are acute. Importing Australia's prohibition playbook wholesale could mean denying young Africans access to tools that, thoughtfully deployed, might accelerate everything from skills development to entrepreneurship.

Policymakers watching Australia's experiment should track what happens next: whether determined teenagers migrate to VPNs, foreign services, and falsified ages; whether the legal challenge gains traction; whether promised mental health benefits materialise or underlying issues simply find new outlets.

I'm not rooting for the prohibition to fail. But I suspect it will prove leakier and more contentious than its architects hope. The hooting doesn't stop because you've banned hooters. It stops when drivers discover that silence gets them home faster.

Editorial Note: A version of this opinion editorial was first published by Business Report on 09 December 2025.