OP-ED: Unpacking the challenges of asset-light models in Africa feat. Abderrahmane Chaoui

Discover why popular "asset-light" business models, celebrated for their scalability, often falter in Africa's unique landscape, as Abderrahmane Chaoui shares his insightful analysis.

Meet Abderrahmane Chaoui

About three years ago, I was introduced to Abderrahmane Chaoui by our mutual friend, Ammin Youssouf. At the time, I was Head of Community at the Pan-African venture capital (VC) firm 54 Collective, and our first conversation felt like one of those long-overdue exchanges that help make sense of the complex and often fragmented nature of African entrepreneurship.

Chaoui, who was two-thirds of the way through a 1.5-year, 13-country research tour across the continent at the time, shared his observations about the stark chasm between North Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa—culturally, linguistically and economically. We bonded over wanting to bridge these divides, particularly the insight and commercial opportunity gaps between Anglophone and Francophone Africa.

His journey was fascinating. After growing up in Algeria and earning a degree from EDHEC Business School in France, Chaoui went on to build a career spanning founding a biotech startup and advising large corporations in over 10 industries on their (innovation) strategy at Fabernovel, an innovation agency in Paris. But it was his on-the-ground exploration of the continent with Sendemo - a research consultancy he founded - that really piqued my interest. His time studying African entrepreneurial ecosystems by spending months at a time interviewing founders, investors, government officials and support organisations - including those in lesser-explored markets like Senegal, Côte d'Ivoire and his home country, Algeria - offered a fresh lens through which to view the continent’s varied startup landscape.

This wasn’t your typical Silicon Valley-inspired hype dive. It was real, nuanced, and shaped by the unique challenges and opportunities present across our continent. Since then, Chaoui’s research has evolved into an invaluable asset for organisations like MIT and 54 Collective, but his insights remain grounded in the realities of doing business in Africa—where infrastructure, financial inclusion and education systems are far from the standards assumed by many global investors.

In this TechTides column hijack, he breaks down why the increasingly popular "asset-light" business models, hailed for their scalability and minimal resource requirements, often struggle to gain traction in Africa.

Chaoui’s insights. In his words:

"Software is eating the world." With these words in 2011, Marc Andreessen, co-founder of Andreessen Horowitz (investor in Facebook, Skype, Twitter), predicted the dominance of software companies in the global economy. Since then, these "high-growth, high-margins, highly-defensible" businesses have seen unprecedented market valuations, proving Andreessen's predictions both lucrative and inspiring for a generation of founders and investors.

A hyper-scalable business operating with minimal labour and physical assets has long been an investor's dream. Software and technology have made this commonplace.

From software to scalable asset-light business models

Software is scalable, intimate and programmable. Cloud technology made it universal, and AI is making it autonomous.

For businesses, this means distribution at scale with zero marginal cost. It allows for intimate customer relationships through data collection and analysis. It's rapidly updatable and adaptable to various use cases. Now theoretically accessible to all simultaneously, it became even more attractive with the advent of generative and self-improving AI models.

Unsurprisingly, founders are striving to incorporate core software components into their businesses, making them "asset-light".

Financially, asset-light models offer the highest total shareholder returns. They require less capital to start and less cash flow to operate, while offering recurring revenues through the SaaS business model.

In essence, software enables more efficient operations and cash management - lowering costs and increasing revenue - while offering potentially unlimited market valuations.

In the past 15 years, nearly every industry has undergone an ‘asset-lightisation’ attempt, transferring core and non-core capabilities into software: mobility, housing, retail, distribution, food. Today, there isn't an industry without a startup presenting itself as asset-light and pursuing VC funding. They typically take the form of SaaS models, both B2B and B2C, followed by financial services (fintech, insurtech) and various marketplaces.

Asset-not-so-light

One often overlooked aspect is that asset-light models can only thrive in fully furnished environments.

To be built, distributed, operated or consumed, a software product needs reliable and sophisticated infrastructure (data centres, networks, cloud technology, high-speed internet and electricity). To be profitable, it needs a banked and solvent target population, sophisticated corporate demand, and financial partners on the ground. For adoption, it requires a population educated in software use and trusting of such tools.

Africa lags behind on each of these points, even in headline economies like South Africa and Egypt.

Yet, 80% of investments in African startups come from investors outside Africa, with mindsets, approaches and strategies forged in different, fully furnished environments. Moreover, foreign late-stage VCs still represent the main exit opportunity for African early-stage funds.

This means that despite market differences, entrepreneurship in Africa is still being shaped by foreign investors' investment theses.

The rush into asset-light models in Africa, visible in pretty much every industry (logistics, trade, financial services, agritech, etc), often leads to disillusionment for founders and investors alike.

Kwely: A case study glance

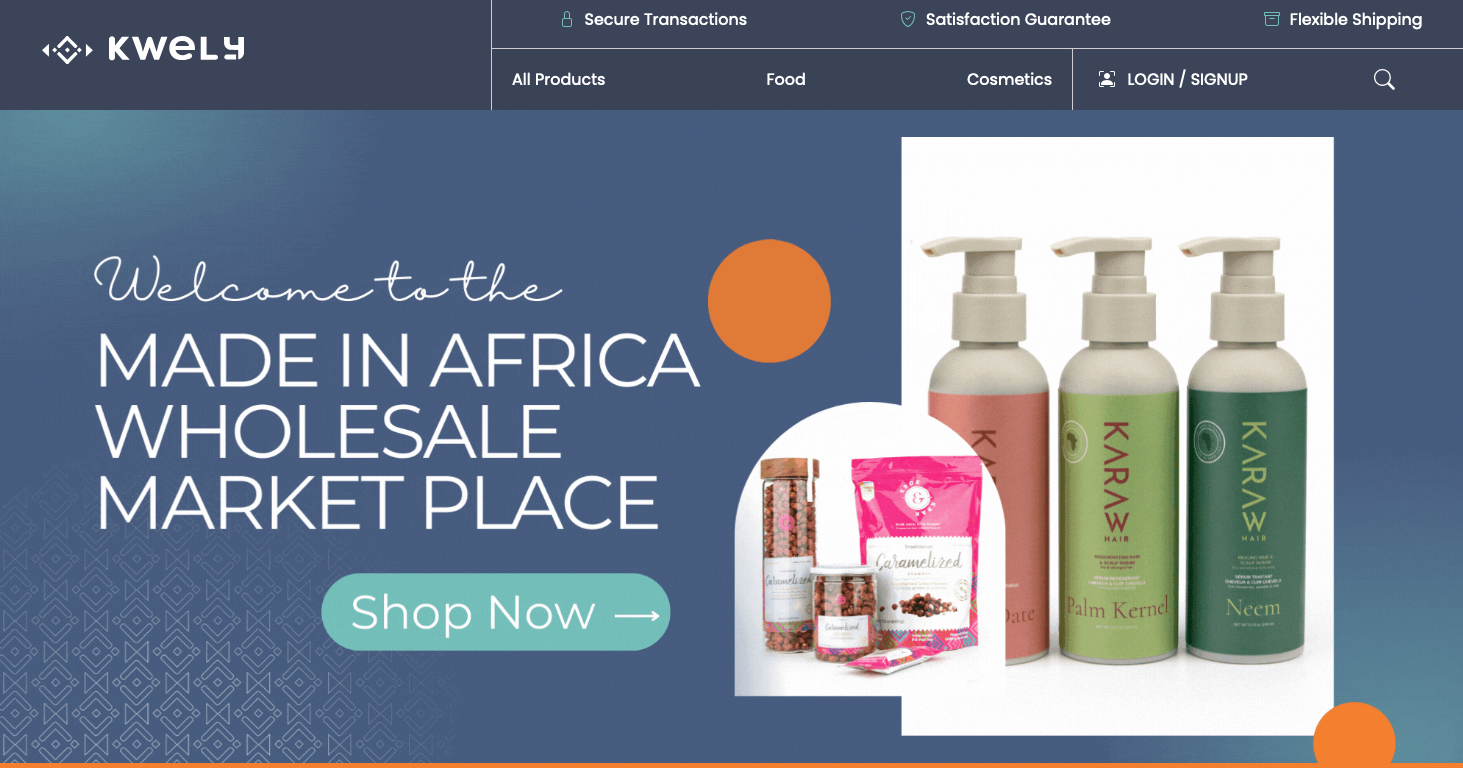

Kwely, a Senegalese B2B marketplace for African products, illustrates this challenge. Founded in 2019 by Birame Sock, a serial entrepreneur with multiple exits in the US, Kwely aimed to become the Alibaba for African products.

When Sock engaged with vendors in Senegal and buyers in the US, she realised Kwely wasn't just about building a tech platform; it was about constructing the entire export value chain from Senegal to the US. Kwely quickly expanded beyond a B2B wholesale marketplace to include:

1. A packaging studio for US-standard packaging

2. A marketing company to build strong brands for new markets

3. An incubator to assist vendors in upgrading production and distribution capacities

4. A US sales arm to educate large distributors on African products

None of these components were in Kwely's original business plan, nor were they understood by investors "only interested in the tech component of the business", even though they recognised these activities were essential for the platform's success.

The way forward

Does this mean the potential for African products lies solely in the scalability of a tech platform? No, it means that most VCs, as currently structured, are not interested in funding the asset-heavy, time-consuming activities embedded in the business models of startups like Kwely.

Pragmatically, exit strategies must be embedded in entrepreneurial models from the start, which means adapting to some extent to foreign late-stage investors' investment theses.

Until more African exit opportunities emerge, innovation in investment mechanisms is crucial. We need to find a way to fund the "unfundable" - businesses building missing value chain components and investing time and effort to educate markets on new processes or business models. This likely requires a combined approach from corporates, private equity and development finance institutions’ (DFIs) more patient capital.

For entrepreneurs, one option is to branch out different business units, making them independently sustainable. Another is to explore joint ventures between corporates and startups or among startups themselves, aiming to reduce the weight of resource-intensive unexpected activities.

Most importantly, foreign investors interested in Africa must adapt their mindset and educate themselves on the continent's specificities and its 54 nuances. Entrepreneurship in such a different business environment doesn't follow the same rules for building, scaling, investing or exiting.

The opportunities remain vast, but the approach must evolve, as perfectly illustrated by Kwely's example. To Kwely and similar ventures pushing boundaries in African entrepreneurship, we wish great success!

Editorial Note: A version of this opinion editorial was first published by Business Report on 24 September 2024.